29 Nov Blatchford makes herself useful

In the PMO War Room, columnist Christie Blatchford must have seemed an inspired choice. She can turn a purple phrase with the best of them. She stands foursquare for troops, widows, and orphans. She’s against plummies, toffs, and pointyheads. She’s long on guts and glory, short on assay. She has an ego as big as the Ritz, and fragile as a Gruyère Soufflé. To receive a document drop on a Matter of National Importance would be sweet validation.

So the Harper Government—someone in the Harper Government—got the brilliant idea of handing Blatchford a trove of Richard Colvin’s long-sought emails from Kandahar, the same documents Harper has thus far refused to surrender to Parliament.

This is a standard bit of hardball damage control. Before releasing damning documents to anyone who might review them critically, pass them instead to a compliant journalist—a “high-value third-party,” in PR lingo—who can be counted on to convey their content with government-friendly gloss.

Blatchford did not disappoint. Her piece in Saturday’s Globe is replete with snide references to Colvin, who did not spend enough time outside the wire for her liking. Apparently volunteering to step into the shoes of the highest ranking diplomat ever to be killed in Afghanistan isn’t sufficient for our combat-besotted scribe.

Blatchford did not disappoint. Her piece in Saturday’s Globe is replete with snide references to Colvin, who did not spend enough time outside the wire for her liking. Apparently volunteering to step into the shoes of the highest ranking diplomat ever to be killed in Afghanistan isn’t sufficient for our combat-besotted scribe.

Blatchford says the document drop “appears to be the entire collection” of Colvin’s Afghan e-mails. Journalists who have actually followed the torture testimony confirm that she appears to have some documents not among those previously released, but she is also missing others. Even by Blatchford’s own account, the documents she got range from “virtually completely blacked out” through “heavily redacted” to [snideness alert] “rattl[ing] on at such length they could have done with a little more redacting.”

The omissions neither trouble Blatchford nor deter her from complaining about what Colvin doesn’t say. She finds nothing in the documents that might have alarmed Colvin’s superiors, noting one memo’s observation that the Kandahar prison was, “not that bad” and “not the worst in Afghanistan.” She somehow overlooked these sections of Memo Kandh-0138:

Of the [redacted] detainees we interviewed, [redacted] said [redacted] had been whipped with cables, shocked with electricity and/or otherwise “hurt”….detainees still had [redacted] on [redacted] body; [redacted] seemed traumatized.

Individual sat with his toes curled under his feet. When he straightened his toe, it could be seen that the nails of the big toe and the one next to it, were a red-orange on the top of the nail, although the new growth underneath appeared fine. When we asked him about his treatment [redacted] rather than Kabul, he became quiet. He said that [redacted] he had been “hurt” and “had problems.” However, he is “happy now.” He did not elaborate on what happened [redacted]. [Redacted] seemed very eager to please, very deferential, and expressed gratitude for our visit. General impression was that he was somewhat traumatized.

When we asked him about his treatment [redacted] he said he had “a very bad time. They hit us with cables and wires.” He said they also shocked him with electricity. He showed us a number of scars on his legs, which he said were caused by the beating. He said he was hit for [redacted] days….

He and others told [redacted] that three fellow detainees had had their fingers “cut and burned with a lighter”….When we asked about his own treatment [redacted] he said that he was hit on his feet with a cable or a “big wire” and forced to stand for two days, but “that’s all.” He showed us a mark on the back of his ankle, which he said was from the cable. [Note: There was a dark red mark on the back of his ankle.] [Hat tip: Dawg’s Blawg & Voice from the Pack.]

Blatchford gloats that Colvin’s most prolific period as a memo-writier dates from a period in 2007 after Globe and Mail reporter Graeme Smith began filing reports on Afghan abuse of detainees arrested by Canadian soldiers. This may or may not be true, given that Blatchford is clearly missing half of Colvin’s 2006 reports (and God knows what else). It also shows remarkable intellectual flexibility, given that Blatchford believes nothing bad ever happened to the Afghans we arrested. The mere mention of Smith’s compelling reportage to the contrary must be embarrassing to her.

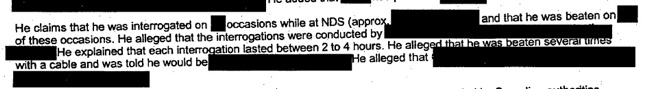

The redactions are interesting. Let’s call this fellow Detainee 1:

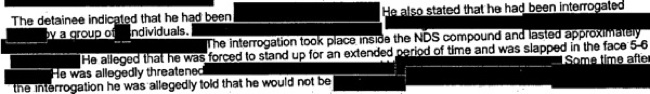

And this fellow Detainee 2:

What exactly are the national security imperatives that prevent disclosure of what Detainee 1 was told after his several beatings, and what he alleged? Why is it vital to Canada’s security that we not know how many men interrogated Detainee 2, or for how long? He was allegedly threatened [blank] and, some time after the interrogation, told that he would not be [blank]. Why doesn’t the government want to fill in these blanks?

There is a bigger issue here than whether one gullible columnist wants to abet Harper’s assassination of one diplomat’s character. For weeks, the opposition MPs who constitute a majority in the House of Commons, our only elected federal institution, have been trying to get their hands on the relevant documents. For weeks Harper has put them off, promising eventual delivery while insisting that General Rick Hillier and Ambassador David Mulroney give their evidence before MPs had a chance to study the documentary record.

“The government has. and will continue. to make all legally available information available.” Harper told the Commons.

Now suddenly the unreleased documents turn up in a friendly (and not very sophisticated) columnist’s inbox. All the pious fretting about national security was, bluntly, a lie; the real concern all along was damage control—even when the issue at hand is Canadian complicity in torture.

Footnote: On the Globe’s website, conservative blogger Norman Spector pleads with Harper for the third time to call an inquiry into the torture allegations. Spector warns of a cloud on the horizon in the form of a Wall Street Journal report that Luis Moreno Ocampo, chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, “is already conducting a ‘preliminary examination’ into whether NATO troops… may have to be put in the dock” over torture allegations.