22 Apr What’s up with all the perfect games lately?

Philip Humber of the Chicago White Sox pitched a perfect game against the Seattle Mariners yesterday. He faced only 27 batters, and got them all out. It’s an exceedingly rare feat—Humber’s was only the 19th in modern Major League Baseball history—but not as rare as it used to be. Or is it?

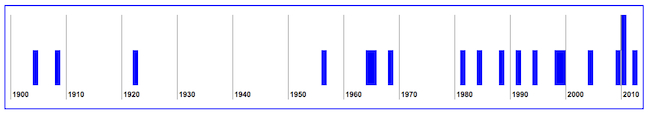

(Click on the chart to view a full-sized version.)

In the first 60 years after the turn of the 20th Century, only four major-leaguers managed to pitch perfect games; 15 have done it in the 62 years since. It sure looks as if pitching a perfect game got easier around 1980, but mathematicians argue that this is just an example of a Poisson distribution, which could be crudely stated as the tendency for rare events to appear non-random.

Writing in the Journal of Statistics Education, Michael Huber of Muhlenberg College and Andrew Glen of the United States Military Academy at West Point examined three other rare baseball feats: no-hitters; triple plays; and hitting for the cycle. None of these is nearly so unusual as a perfect game, but all three:

offer excellent examples of events whose occurrence may be modeled as Poisson processes. That is, the time of occurrence of one of these events doesn’t affect when we see the next occurrence of such.

When two perfect games occurred in 2010, statistician Martin Monkman of British Columbia took a similar view in his aptly named Bayes Blog.

As for Humber, his pristine performance at the Mariners’ Safeco Field took just two hours and 17 minutes.

“My wife is nine months pregnant,” he explained, “and I was making sure she didn’t give birth when I was pitching,”