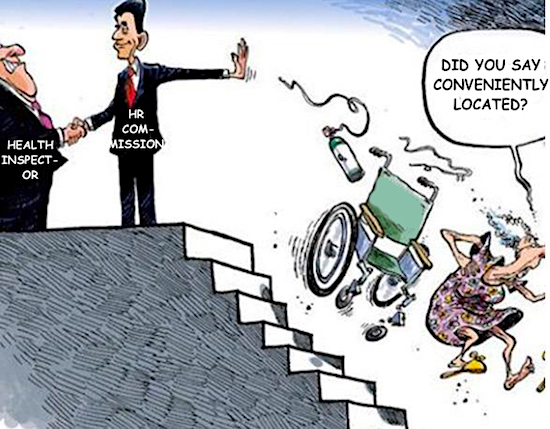

27 Oct How Nova Scotia’s Human Rights Commission impedes disability rights

Human rights lawyer David Fraser has filed an action in the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia seeking a review of the NS Human Rights Commission’s refusal to accept a complaint against the province by five prominent disability rights activists.

The complaint is a tad complex, but it aptly illustrates Nova Scotia’s stonewalling of people with disabilities: the failure of municipal building inspectors to enforce barrier-free requirements of the building code; the political failure of provincial and federal governments to give those regulations teeth; and the inexplicable failure of the Human Rights Commission to show leadership in this area—or even accept complaints about it.

In brief, the Food Safety Regulations under s. 105 of the Health Protection Act require restaurants to have a conveniently located washroom for customers, one that meets the building code. Many restaurants are exempt from the barrier-free requirements of the building code because they are “grandfathered” as pre-existing, non-conforming uses. However, when restaurants add seasonal sidewalk patios, a bylaw requires the patios to be barrier free in compliance with the Canada Building Code. This leads to a profusion of Halifax restaurants that admit people using wheelchairs, but do not provide them with conveniently located, barrier-free washrooms.

In brief, the Food Safety Regulations under s. 105 of the Health Protection Act require restaurants to have a conveniently located washroom for customers, one that meets the building code. Many restaurants are exempt from the barrier-free requirements of the building code because they are “grandfathered” as pre-existing, non-conforming uses. However, when restaurants add seasonal sidewalk patios, a bylaw requires the patios to be barrier free in compliance with the Canada Building Code. This leads to a profusion of Halifax restaurants that admit people using wheelchairs, but do not provide them with conveniently located, barrier-free washrooms.

The health authorities insist this is a building code issue. The complainants contend its a human rights and a health protection issue.

Being able to wash one’s hands before eating is a well-established health priority. A few summers ago, two posh Halifax restaurants were shut down when staff and customers contracted Norovirus. Handwashing was the remedy our health authorities prescribed.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but the opportunity to wash one’s hands before eating especially important for people who use wheelchairs. Many people with disabilities are unusually susceptible to infections. Moreover, their hands come into contact with the wheels of their chairs, which in turn come into contact with whatever doggie residues inhabit the mean streets of Halifax. But, really, don’t we all want everyone to wash their hands, not just ourselves?

The complainants deliberately declined to complain against the individual noncomplying restaurants (Effendy, The Wooden Monkey, Le Coq, and The Five Fishermen) but rather complained against the Chief Medical Office of Health and the Minister of Environment (who is responsible for food safety inspections) for failing to enforce the regulations. The Human Rights Commission twice rejected the complaint on grounds that complaints about administration of government programs should go to the Ombudsman. The complainants replied that they were complaining about discriminatory administration of government programs, an issue over which the Nova Scotia Human Rights Act has jurisdiction.

Depart copulating, said the HR Commission. So with lawyer Fraser’s help, the complainants are suing.

Complainer-in-Chief Gus Reed has been my friend for three decades. You can’t be Gus’s friend without getting drawn into his tenacious demands for equal treatment of wheelchair users. Gus lives half the year in Halifax and half in North Carolina, where the Americans with Disabilities Act gives him easy access to speedy official enforcement of accessibility rules. Here in Nova Scotia, he faces lip service to disabilities rights undergirded by non-enforcement of the wishy-washy rules we have. Building inspectors won’t enforce barrier-free regs because, when they do, the business people complain to their councillors, and the inspector soon has an annoyed politician on his case.

Sailor Bup’s: No wheelchair users need apply

Non-enforcement is half the problem. The other half is the building code’s grandfather provision, which applies to so many buildings in Halifax because it’s such an old city. Because the grandfather clause has no sunset provision, exemption from barrier-free requirements becomes a permanent asset that enhances a building’s real estate value. It gets passed from owner to owner in perpetuity—as long as the building remains some sort of retail establishment. When the inaccessible surf shop at Queen and Morris became a candy shop, officials deemed it not to be a change of use. When three different Halifax building inspectors found three different sets of violations at Sailor Bup’s Dartmouth barbershop, not one cited its glaring lack of a ramp, even though there is plenty of room for a ramp and modest ramp is all that’s needed. If the rumoured settlement of Bup’s feud with the city comes to fruition, I’ll bet dollars to Timbits the solution won’t include a ramp.

Quite apart from the human rights and health issues here, consider the lost strategic opportunity. As long as it is grandfathered, an inaccessible restaurant has a financial incentive to retain barriers to wheelchairs. But if provincial inspectors took the logical step of insisting restaurants with accessible patios must have accessible washrooms, accessibility would have a powerful financial incentive on its side. The city and the province could say to restaurateurs, “Sidewalk patios are lucrative; if you want one, invest in an accessible washroom.”

One final word about the Human Rights Commission. Its two decisions refusing to accept a complaint from the disability rights activists in this case are so convoluted, illogical, and twisted as to betray a determination to let provincial government obstructors slip the hook. One hopes the Supreme Court will make short work of this dereliction, but whatever the outcome, it remains troubling behaviour by a body charged with sticking up for the rights of those least able to speak up for themselves.