03 Jun Pushback on electoral equality

On Saturday, I wrote that the majority members of the Nova Scotia Electoral Boundaries Commission only pretended to “interpret” their Terms of Reference, when in fact they had openly disregarded them. Their only ethical choice, I wrote, was to “resign from the commission; or swallow hard and complete their assigned task.”

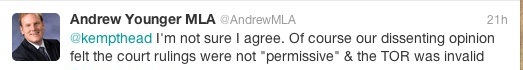

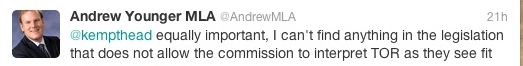

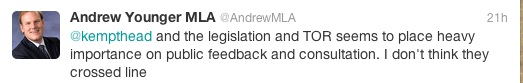

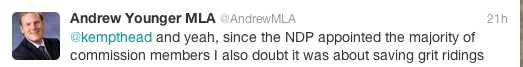

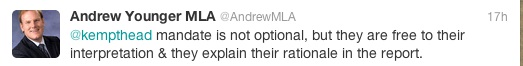

Important members of both opposition parties have responded. Liberal MLA Andrew Younger did so in a series of tweets:

In fact, Canadian courts have ruled that +/- 25 percent should be the normal limit for variations in riding sizes, but that legislatures may go beyond that limit in special circumstances. It didn’t say they have to. The Nova Scotia Legislature could have done so in this case, but it didn’t. The Terms of Reference that established the commission specifically ruled out ridings that varied more then 25 percent from the average population. Nowhere does the legislation say the Terms of Reference given the commission are optional.

Rob Batherson, former Communications Director for Premier John Hamm, made the Conservative Party’s case in an email:

1) The Commission was operating under terms of reference that were set by the Legislative Select Committee, without all-party consent, which had been the convention in the previous two rounds of redistribution (1991-92 and 2001-02), both of which operated in majority government environments.

2) The NDP used their majority on the Select Committee to insert clause 2(d) during an in camera meeting prior to New Year’s Eve over the objections of the two opposition parties. I suggest this is a level of political gamesmanship that we had successfully gotten away from with the amendments to the House of Assembly Act put in place by Don Cameron’s government in the early 1990s.

3) It is highly inappropriate for the Minister of Justice to demand his own private meeting with the Commission Chair. The Commission is accountable to the Select Committee consisting of MLAs from all parties.

4) Clause 2(f) of the terms of reference of the Commission states:

“All submissions to the Commission from individuals and organizations be made in public.”

If the Minister wishes to articulate his government’s position, he is required to do so publicly, not behind close doors.

5) The government erred considerably in its drafting of the terms of reference, using the conditional “may not deviate” from the plus or minus 25 per cent population variance, instead of the more definitive “shall not deviate.” This provides the Commission with flexibility in interpreting that clause.

6) No less a credible New Democrat than former Preston MLA and leadership candidate Yvonne Atwell admitted several months ago to CBC’s Paul Withers that she didn’t think the NDP government would be going to such lengths to eliminate the constituencies of Preston, Argyle, Clare and Richmond were any of them currently represented by New Democrats.

The government has a legitimate case to make on why it unilaterally decided to set the terms of reference as it did and why it expects the Commission to adhere to those terms. But it should do so openly, subject to public scrutiny, rather than in secret. In the meantime, the Commission is completely within its rights to provide recommendations to the House of Assembly, free of the political considerations that are obviously motivating government’s decision to break from 20 years of precedent on electoral redistribution.

Points 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6, may ro may not be valid, but they are crimson gaspareaux, scattered along the rhetorical trail to distract us core issue: whether the commission had the authority to treat its mandate as optional. Point 5 makes the legalistic claim that sloppy drafting gave the commissioners wiggle room. I think the meaning of “may not deviate” is plain enough, and I suspect any court will agree.

Finally, a curmudgeonly friend writes:

Had the Electoral Boundaries Commission complied with the terms of reference handed to it by the legislature, it could have quietly put to death a divisive and arbitrary status quo.

Let’s start with arbitrary. Nova Scotia’s First Nations people outnumber any other group in the province that could be defined by the construct of race, and their memories of grotesque abuse by the state are just as fresh as, say, those of the former residents of Africville. So, where are “protected constituencies” for First Nations?

Divisive: two of the three tiny ridings purportedly protected for the benefit of francophones are actually dominated by people who speak only English in their homes. I could say more along those lines — the stats are easy to find — but I guarantee that nothing beneficial will come from that kind of discourse. The commission, however, seems ready to take us there.

Inequities, apparent or real, cannot be addressed by creating electoral “homelands,” to use the unfortunate language of the commission’s interim report. If the commission wants to ignore the clear instructions given to it by the House of Assembly, it will have to come up with something more creative.

It’s also worth noting that the four “protected” ridings have a combined population equal to two “ordinary” ones. That suggests that Nova Scotia could get by with 50 ridings instead of 52, a recommendation that would be within the commission’s legal terms of reference.

To put this argument a different way, fewer than 25 percent of the 9,600 residents in the protected riding of Richmond list their mother tongue as either “only French” or “both French and English.” Whitney Pier, with roughly the same number of residents, boasts the richest multicultural population in Atlantic Canada. To preserve the tiny Richmond Riding, with 50 percent fewer voters than the average riding, the Commission eliminated Cape Breton Nova, which is to say, Whitney Pier. This is the sort of calculus we fall into once we put our thumb on the scale on behalf of favored ethnic groups.

If we truly want to ensure a voice for geographically dispersed ethnic populations in Nova Scotia, we could switch to proportional representation, a system with its own set of pluses and minuses.

Batherson has a point when he abjures the Minister of Justice not to meet with the commission behind closed doors. By the same token, the two opposition parties should think hard before launching a partisan campaign for special ethnic status. To call the government’s action in eliminating the seats gerrymandering is to stand reality on its head; It’s the four protected seats that are gerrymandered. By any reasonable counting method, even one that accommodates large, sparsely populated districts, urban Halifax is underrepresented in the House or Assembly.