04 Mar Proof that it’s never to late to correct a factual error

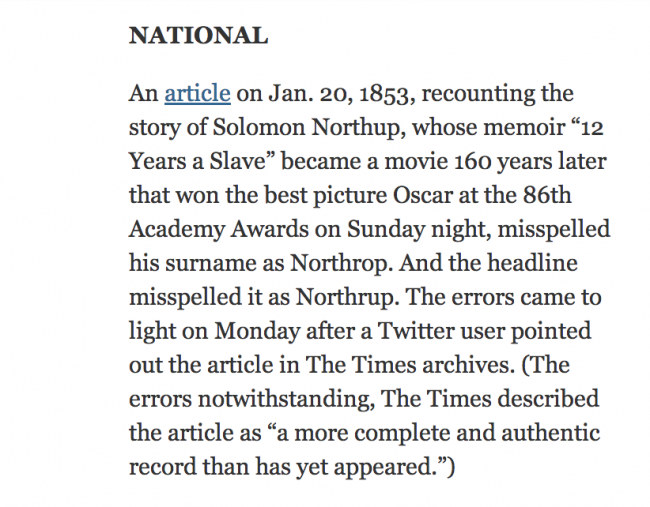

The New York Times this morning published a correction of a story it ran 161 years ago, on January 20, 1853:

The Times does take its responsibility for factual accuracy seriously. This whimsical correction of two, 161-year-old spelling errors was one of nine corrections it published today. Five years ago, at the urging of Contrarian and Provincial Court Judge Anne Derrick, the Times corrected its obituary of Donald Marshall Jr. The original version of the Times obit had incorrectly described the circumstances surrounding the killing of Sandy Seale, the 16-year-old boy whom Marshall was falsely convicted of murdering.

For all they criticize others, journalists have notoriously thin skins. They hate admitting error. Certain local journals all but refuse to do so unless someone credibly threatens litigation. Yet here comes the august New York Times publishing fistsful of mea culpas day after day. Far from diminishing its credibility or exposing the paper as sloppy, this willingness to admit and correct mistakes enhances its stature.

The Times published tens of thousands of words a day about fast-breaking, important, often controversial events. It is not humanly possible to do that without making mistakes. By correcting them forthrightly, the Times show readers a commitment to get things right.

To be sure, many critics say the Times gets a lot of big things wrong, such as its reluctance to apply the term “torture” to brutal tactics employed by the US Military. I agree with some of this criticism, but they are matters of editorial judgment and opinion. I am still grateful for the paper’s determination to ferret out and fix even the smallest factual mistakes.

The gold standard for correction goes to the Public Radio International program This American Life, which discovered it had been grossly misled by a freelancer in an episode that purported to expose abuse of factory workers in China. The program didn’t merely correct, retract, and apologize for the story. It did all of those things, but it also devoted a full hour to a meticulous examination of the fabrication, and its producers’ failure to realize they were being hoodwinked. The correction is a remarkable piece of journalism in its candour, thoroughness, and willingness to shine an unflattering spotlight on its own journalistic failings. Ironically, it gave me an almost unshakable trust in the program. You can listen to the correction here, and download the transcript here. You can subscribe to the podcast with iTunes or any podcast app.