16 May Pundits’ Guide begs the question

Last Thursday, Contrarian got into a bit of a Twitter dustup with Alice Funke, whose blog, Pundits’ Guide, features statistical analysis of Canadian election results.

In a post titled, “Mommy, They Split My Vote,” Funke purported to show that few if any of the 27 Liberal seats lost to Stephen Harper’s Conservatives in the May 2 election had been lost due to vote-splitting. Her complicated argument defies succinct exegesis, but you can read it here.

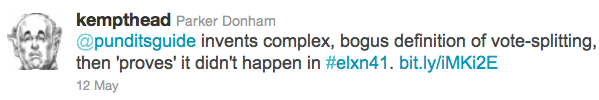

In response, I tweeted:

This unleashed a torrent of counter-tweets that, for the time being at least, you can find here and here (by scrolling back to May 12). Funke followed up with an email buttressing her position (which I quote with her permission):

Of course in a multi-party, first-past-the-post electoral system, there are seats won by less than 50%. But the people currently arguing that “vote-splitting amongst ‘the left’ is allowing the Conservatives to win”, honestly do not know their election result data.

Outside of the very few core urban seats in Canada, where the Liberal vote falls off, it largely falls off to the Conservatives’ benefit, or stays home to their benefit. So, there are vote splits alright, but on the right-hand side of the spectrum. But this is not what was being argued as the cause of those Liberal seats falling…

[Y]ou can’t simply add the Liberal and NDP votes in any given election together, because for the “vote-splitting” argument to work you need to prove that any voters who stayed home in 2008 but showed up to vote this time, would have also showed up to vote in the case where there was a single, let’s say Liberal, choice on the ballot.

In the suburban Toronto and 905 seats I presented in detail, either:

* the Conservative vote hikes came from Liberals, and the NDP gains came from previous non-voters and previous Greens, or

* the Conservative vote hikes came from previous non-voters and previous Greens, and the NDP gains came from Liberals

Mathematically, there are no other generalized possibilities.

If there were a preferential ballot in Canada, and there were no more “vote splits” by your definition, it is not at all clear that it would have the outcome everywhere that you believe. In core urban seats, yes. But they are not the majority of ridings in Canada, though everyone who spouts the current version of the vote-splitting argument seems to come from one and believes that voting pattern to be universal. It’s not.

I do not quarrel with Funke’s arithmetic. My problem is that she begs the question.* That is to say, her definition of vote-splitting is so narrow as to all but guarantee the result she found. To certify a loss as one due to vote-splitting, Funke requires two conditions:

- The party gaining the seat does so by gaining fewer votes than the party losing the seat loses, and that

- Some third party gains more votes than the losing party loses

When we encounter a definition this odd and this technical in a blogpost with the churlish title “Mommy, They Split My Vote,” we may be forgiven for wondering if it was devised to be unmeetable (at least in a transformative election).

Many Canadians would define vote-splitting as any seat where a Harper candidate beat a Liberal or NDP incumbent but took less than 50 percent of the vote. I am inclined to accept Funke’s point that such outcomes are inevitable in a first-past-the-post election with three or more parties.

In the context of the election just past however, vote-spitting could be reasonably defined as any seat where a Harper candidate beat a Liberal incumbent by a margin smaller than the increase in that riding’s NDP vote. A tally of ridings fitting this definition would be illuminating, as would knowing whether Harper would have a majority without them.

By election day, everyone could predict that the Liberals and the Greens would shed votes, the NDP would gain, and the Harperists would either hold or gain. Given those assumptions, it was all but certain the Liberals would lose seats. In some cases, it seemed likely they would lose seats to the Conservatives because too many previously Liberal or Liberal-inclined voters would defect to the NDP.

Such shifts are, to a large extent, hypothetical. The electorate in each riding has changed in the two and a half years since the last vote. Some voters have died, others have come of age, moved in, moved out, attained citizenship, etc. In both elections, many voters stayed home for a multitude of reasons. Those who voted Liberal in 2008 but deserted the party this year may have moved to the NDP, the Harperists, or the Greens—or they may have stayed home altogether. Attempts to parse these shifts without detailed exit surveys are a mug’s game, and given voters’ notoriously faulty reporting, they are problematic even with exit surveys in hand.

But in a highly polarized electorate, where the defunct centre right party has been taken over by the hard right, and where the centrist party in steep decline, it’s legitimate for progressive voters to worry that a shift of anti-Harper votes from Liberal incumbents to NDP also-rans could have the unintended effect of letting Harper candidates slip up the middle to victory.

For millions of Canadians, fear of giving an unchecked majority to a hard right party led by an uncompromising authoritarian trumps their loyalty to either the Liberals or the NDP. Their concerns are legitimate. Pundits’ Guide would perform a service by quantifying them, rather than simply pooh-poohing them.

—

* Please note rare quasi-correct use of this figure of speech.